Network address translation

In computer networking, network address translation (NAT) is the process of modifying network address information in datagram (IP) packet headers while in transit across a traffic routing device for the purpose of remapping one IP address space into another.

Most often today, NAT is used in conjunction with network masquerading (or IP masquerading) which is a technique that hides an entire IP address space, usually consisting of private network IP addresses (RFC 1918), behind a single IP address in another, often public address space. This mechanism is implemented in a routing device that uses stateful translation tables to map the "hidden" addresses into a single IP address and readdresses the outgoing Internet Protocol (IP) packets on exit so that they appear to originate from the router. In the reverse communications path, responses are mapped back to the originating IP address using the rules ("state") stored in the translation tables. The translation table rules established in this fashion are flushed after a short period unless new traffic refreshes their state.

As described, the method enables communication through the router only when the conversation originates in the masqueraded network, since this establishes the translation tables. For example, a web browser in the masqueraded network can browse a website outside, but a web browser outside could not browse a web site in the masqueraded network. However, most NAT devices today allow the network administrator to configure translation table entries for permanent use. This feature is often referred to as "static NAT" or port forwarding and allows traffic originating in the "outside" network to reach designated hosts in the masqueraded network.

Because of the popularity of this technique (see below), the term NAT has become virtually synonymous with the method of IP masquerading.

Network address translation has serious consequences, both drawbacks and benefits, on the quality of Internet connectivity and requires careful attention to the details of its implementation. As a result, many methods have been devised to alleviate the issues encountered. See the article on NAT traversal.

Contents |

Overview

In the mid-1990s NAT became a popular tool for alleviating the problem of IPv4 address exhaustion. It has become a standard, indispensable feature in routers for home and small-office Internet connections.

Most systems using NAT do so in order to enable multiple hosts on a private network to access the Internet using a single public IP address (see gateway). However, NAT breaks the originally envisioned model of IP end-to-end connectivity across the Internet, introduces complications in communication between hosts, and affects performance.

NAT obscures an internal network's structure: all traffic appears to outside parties as if it originated from the gateway machine.

Network address translation involves over-writing the source or destination IP address and usually also the TCP/UDP port numbers of IP packets as they pass through the router. Checksums (both IP and TCP/UDP) must also be rewritten as a result of these changes.

In a typical configuration, a local network uses one of the designated "private" IP address subnets (RFC 1918). Private Network Addresses are 192.168.x.x, 172.16.x.x through 172.31.x.x, and 10.x.x.x (or using CIDR notation, 192.168/16, 172.16/12, and 10/8), and a router on that network has a private address (such as 192.168.0.1) in that address space. The router is also connected to the Internet with a single "public" address (known as "overloaded" NAT) or multiple "public" addresses assigned by an ISP. As traffic passes from the local network to the Internet, the source address in each packet is translated on the fly from the private addresses to the public address(es). The router tracks basic data about each active connection (particularly the destination address and port). When a reply returns to the router, it uses the connection tracking data it stored during the outbound phase to determine where on the internal network to forward the reply; the TCP or UDP client port numbers are used to demultiplex the packets in the case of overloaded NAT, or IP address and port number when multiple public addresses are available, on packet return. To a host on the Internet, the router itself appears to be the source/destination for this traffic.

Basic NAT and PAT

There are two levels of network address translation.

- Basic NAT. This involves IP address translation only, not port mapping.

- PAT (Port Address Translation). Also called simply "NAT" or "Network Address Port Translation, NAPT". This involves the translation of both IP addresses and port numbers.

All Internet packets have a source IP address and a destination IP address. Both or either of the source and destination addresses may be translated.

Some Internet packets do not have port numbers: for example, ICMP packets. However, the vast bulk of Internet traffic is TCP and UDP packets, which do have port numbers. Packets which do have port numbers have both a source port number and a destination port number. Both or either of the source and destination ports may be translated.

NAT which involves translation of the source IP address and/or source port is called source NAT or SNAT. This re-writes the IP address and/or port number of the computer which originated the packet.

NAT which involves translation of the destination IP address and/or destination port number is called destination NAT or DNAT. This re-writes the IP address and/or port number corresponding to the destination computer.

SNAT and DNAT may be applied simultaneously to Internet packets.

Types of NAT

Network address translation is implemented in a variety of schemes of translating addresses and port numbers, each affecting application communication protocols differently. In some application protocols that use IP address information, the application running on a node in the masqueraded network needs to determine the external address of the NAT, i.e., the address that its communication peers detect, and, furthermore, often needs to examine and categorize the type of mapping in use. For this purpose, the Simple traversal of UDP over NATs (STUN) protocol was developed (RFC 3489, March 2003). It classified NAT implementation as full cone NAT, (address) restricted cone NAT, port restricted cone NAT or symmetric NAT[1] and proposed a methodology for testing a device accordingly. However, these procedures have since been deprecated from standards status, as the methods have proven faulty and inadequate to correctly assess many devices. New methods have been standardized in RFC 5389 (October 2008) and the STUN acronym now represents the new title of the specification: Session Traversal Utilities for NAT.

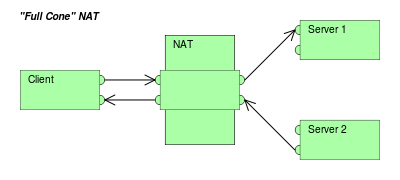

Full-cone NAT, also known as one-to-one NAT

|

|

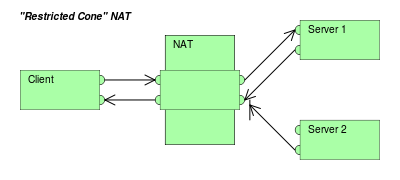

(Address) restricted cone NAT

|

|

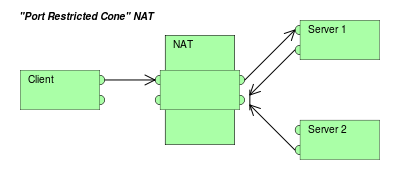

| Port-restricted cone NAT

Like an address restricted cone NAT, but the restriction includes port numbers.

|

|

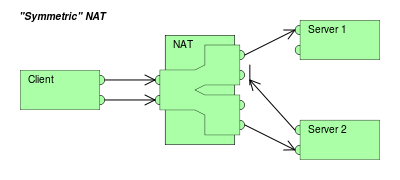

Symmetric NAT

|

|

This terminology has been the source of much confusion, as it has proven inadequate at describing real-life NAT behavior.[2] Many NAT implementations combine these types, and it is therefore better to refer to specific individual NAT behaviors instead of using the Cone/Symmetric terminology. Especially, most NAT translators combine symmetric NAT for outgoing connections with static port mapping, where incoming packets to the external address and port are redirected to a specific internal address and port. Some products can redirect packets to several internal hosts, e.g. to divide the load between a few servers. However, this introduces problems with more sophisticated communications that have many interconnected packets, and thus is rarely used.

Many NAT implementations follow the port preservation design. For most communications, they use the same values as internal and external port numbers. However, if two internal hosts attempt to communicate with the same external host using the same port number, the external port number used by the second host will be chosen at random. Such NAT will be sometimes perceived as (address) restricted cone NAT and other times as symmetric NAT.

NAT and TCP/UDP

"Pure NAT", operating on IP alone, may or may not correctly parse protocols that are totally concerned with IP information, such as ICMP, depending on whether the payload is interpreted by a host on the "inside" or "outside" of translation. As soon as the protocol stack is climbed, even with such basic protocols as TCP and UDP, the protocols will break unless NAT takes action beyond the network layer.

IP has a checksum in each packet header, which provides error detection only for the header. IP datagrams may become fragmented and it is necessary for a NAT to reassemble these fragments to allow correct recalculation of higher-level checksums and correct tracking of which packets belong to which connection.

The major transport layer protocols, TCP and UDP, have a checksum that covers all the data they carry, as well as the TCP/UDP header, plus a "pseudo-header" that contains the source and destination IP addresses of the packet carrying the TCP/UDP header. For an originating NAT to successfully pass TCP or UDP, it must recompute the TCP/UDP header checksum based on the translated IP addresses, not the original ones, and put that checksum into the TCP/UDP header of the first packet of the fragmented set of packets. The receiving NAT must recompute the IP checksum on every packet it passes to the destination host, and also recognize and recompute the TCP/UDP header using the retranslated addresses and pseudo-header. This is not a completely solved problem. One solution is for the receiving NAT to reassemble the entire segment and then recompute a checksum calculated across all packets.

Originating host may perform Maximum transmission unit (MTU) path discovery (RFC 1191) to determine the packet size that can be transmitted without fragmentation, and then set the "don't fragment" bit in the appropriate packet header field.

Destination network address translation (DNAT)

DNAT is a technique for transparently changing the destination IP address of an en-route packet and performing the inverse function for any replies. Any router situated between two endpoints can perform this transformation of the packet.

DNAT is commonly used to publish a service located in a private network on a publicly accessible IP address. This use of DNAT is also called port forwarding.

SNAT

The meaning of the term SNAT varies by vendor. Many vendors have proprietary definitions for SNAT. A common definition is Source NAT, the counterpart of Destination NAT (DNAT). Microsoft uses the acronym for Secure NAT, in regard to the ISA Server extension discussed below. For Cisco Systems, SNAT means Stateful NAT.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) defines SNAT as Softwires Network Address Translation. This type of NAT is named after the Softwires working group that is charged with the standardization of discovery, control and encapsulation methods for connecting IPv4 networks across IPv6 networks and IPv6 networks across IPv4 networks.

Dynamic network address translation

Dynamic NAT, just like static NAT, is not common in smaller networks but is found within larger corporations with complex networks. The way dynamic NAT differs from static NAT is that where static NAT provides a one-to-one internal to public static IP address mapping, dynamic NAT doesn't make the mapping to the public IP address static and usually uses a group of available public IP addresses.

Applications affected by NAT

Some Application Layer protocols (such as FTP and SIP) send explicit network addresses within their application data. FTP in active mode, for example, uses separate connections for control traffic (commands) and for data traffic (file contents). When requesting a file transfer, the host making the request identifies the corresponding data connection by its network layer and transport layer addresses. If the host making the request lies behind a simple NAT firewall, the translation of the IP address and/or TCP port number makes the information received by the server invalid. The Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) controls Voice over IP (VoIP) communications and suffers the same problem. SIP may use multiple ports to set up a connection and transmit voice stream via RTP. IP addresses and port numbers are encoded in the payload data and must be known prior to the traversal of NATs. Without special techniques, such as STUN, NAT behavior is unpredictable and communications may fail.

Application Layer Gateway (ALG) software or hardware may correct these problems. An ALG software module running on a NAT firewall device updates any payload data made invalid by address translation. ALGs obviously need to understand the higher-layer protocol that they need to fix, and so each protocol with this problem requires a separate ALG.

Another possible solution to this problem is to use NAT traversal techniques using protocols such as STUN or ICE, or proprietary approaches in a session border controller. NAT traversal is possible in both TCP- and UDP-based applications, but the UDP-based technique is simpler, more widely understood, and more compatible with legacy NATs. In either case, the high level protocol must be designed with NAT traversal in mind, and it does not work reliably across symmetric NATs or other poorly-behaved legacy NATs.

Other possibilities are UPnP (Universal Plug and Play) or Bonjour (NAT-PMP), but these require the cooperation of the NAT device.

Most traditional client-server protocols (FTP being the main exception), however, do not send layer 3 contact information and therefore do not require any special treatment by NATs. In fact, avoiding NAT complications is practically a requirement when designing new higher-layer protocols today.

NATs can also cause problems where IPsec encryption is applied and in cases where multiple devices such as SIP phones are located behind a NAT. Phones which encrypt their signaling with IPsec encapsulate the port information within the IPsec packet meaning that NA(P)T devices cannot access and translate the port. In these cases the NA(P)T devices revert to simple NAT operation. This means that all traffic returning to the NAT will be mapped onto one client causing the service to fail. There are a couple of solutions to this problem: one is to use TLS, which operates at level 4 in the OSI Reference Model and therefore does not mask the port number; another is to Encapsulate the IPsec within UDP - the latter being the solution chosen by TISPAN to achieve secure NAT traversal.

The DNS protocol vulnerability announced by Dan Kaminsky on 2008 July 8 is indirectly affected by NAT port mapping. To avoid DNS server cache poisoning, it is highly desirable to not translate UDP source port numbers of outgoing DNS requests from a DNS server which is behind a firewall which implements NAT. The recommended work-around for the DNS vulnerability is to make all caching DNS servers use randomized UDP source ports. If the NAT function de-randomizes the UDP source ports, the DNS server will be made vulnerable.

Drawbacks

Hosts behind NAT-enabled routers do not have end-to-end connectivity and cannot participate in some Internet protocols. Services that require the initiation of TCP connections from the outside network, or stateless protocols such as those using UDP, can be disrupted. Unless the NAT router makes a specific effort to support such protocols, incoming packets cannot reach their destination. Some protocols can accommodate one instance of NAT between participating hosts ("passive mode" FTP, for example), sometimes with the assistance of an application-level gateway (see below), but fail when both systems are separated from the Internet by NAT. Use of NAT also complicates tunneling protocols such as IPsec because NAT modifies values in the headers which interfere with the integrity checks done by IPsec and other tunneling protocols.

End-to-end connectivity has been a core principle of the Internet, supported for example by the Internet Architecture Board. Current Internet architectural documents observe that NAT is a violation of the End-to-End Principle, but that NAT does have a valid role in careful design.[3] There is considerably more concern with the use of IPv6 NAT, and many IPv6 architects believe IPv6 was intended to remove the need for NAT.[4]

Because of the short-lived nature of the stateful translation tables in NAT routers, devices on the internal network lose IP connectivity typically within a very short period of time unless they implement NAT keep-alive mechanisms by frequently accessing outside hosts. This dramatically shortens the power reserves on battery-operated hand-held devices and has thwarted more widespread deployment of such IP-native Internet-enabled devices.

Some Internet service providers (ISPs), especially in Russia, Asia and other "developing" regions provide their customers only with "local" IP addresses, due to a limited number of external IP addresses allocated to those entities. Thus, these customers must access services external to the ISP's network through NAT. As a result, the customers cannot achieve true end-to-end connectivity, in violation of the core principles of the Internet as laid out by the Internet Architecture Board.

Benefits

The primary benefit of IP-masquerading NAT is that it has been a practical solution to the impending exhaustion of IPv4 address space. Even large networks can be connected to the Internet with as little as a single IP address. The more common arrangement is having machines that require end-to-end connectivity supplied with a routable IP address, while having machines that do not provide services to outside users behind NAT with only a few IP addresses used to enable Internet access.

Some[5] have also called this exact benefit a major drawback, since it delays the need for the implementation of IPv6, quote:

"[…] it is possible that its [NAT's] widespread use will significantly delay the need to deploy IPv6. […] It is probably safe to say that networks would be better off without NAT […]"

Examples of NAT software

- IPFilter

- PF (firewall): The OpenBSD Packet Filter.

- Netfilter NAT engine

- Internet Connection Sharing (ICS)

- WinGate

See also

- AYIYA (IPv6 over IPv4 UDP thus working IPv6 tunneling over most NATs)

- Carrier Grade NAT

- Firewall

- Gateway

- Internet Gateway Device (IGD) Protocol: UPnP NAT-traversal method

- Middlebox

- Multi-level NAT

- NAT-PT

- Port forwarding

- Private IP address

- Proxy server

- Routing

- Subnet

- Teredo tunneling: NAT traversal using IPv6

References

- ↑ NAT Types (PDF)

- ↑ François Audet; and Cullen Jennings (January 2007) (text). RFC 4787 Network Address Translation (NAT) Behavioral Requirements for Unicast UDP. IETF. http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc4787.txt. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ↑ R. Bush; and D. Meyer; RFC 3439, Some Internet Architectural Guidelines and Philosophy, December 2002

- ↑ G. Van de Velde et al.; RFC 4864, Local Network Protection for IPv6, May 2007

- ↑ Larry L. Peterson; and Bruce S. Davie; Computer Networks: A Systems Approach, Morgan Kaufmann, 2003, pp. 328-330, ISBN 1-55860-832-X

External links

- NAT-Traversal Test and results

- Characterization of different TCP NATs – Paper discussing the different types of NAT

- Anatomy: A Look Inside Network Address Translators – Volume 7, Issue 3, September 2004

- Jeff Tyson, HowStuffWorks: How Network Address Translation Works

- NAT traversal techniques in multimedia Networks – White Paper from Newport Networks

- Peer-to-Peer Communication Across Network Address Translators (PDF) – NAT traversal techniques for UDP and TCP

- RFC 5128 - Informational - State of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Communications across Network Address Translators (NATs)

- RFC 4008 – Standards Track – Definitions of Managed Objects for Network Address Translators (NAT)

- RFC 3022 – Traditional IP Network Address Translator (Traditional NAT)

- RFC 1631 – Obsolete – The IP Network Address Translator (NAT)

- Speak Freely End of Life Announcement – John Walker's discussion of why he stopped developing a famous program for free Internet communication, part of which is directly related to NAT

- natd

- SNAT, DNAT and OCS2007R2 – discussing the SNAT in Microsoft OCS 2007R2

- Alternative Taxonomy